News Page

On this page we will try and keep you informed of some of the items that we think you should be aware of around Northampton in realtion to buildings/events and particular Planning Applications that affect the history of the town.

Our Committee are looking for new members to help us promote the Society. If you are interested in the town and its history and want to help us promote the town, then use our contact page and we will reply with more information. It is not an onerous task, you can see from the events pages when our Committee meetings are and the Events we are holding this year.

If you wish us to raise anything or want to contact us for any reason, please use the contact page, thank you

Newsletter No 5 - September 2025

Our latest newsletter is now available by clicking on the link below - again its in pdf format.

Newsletter No 4 - August 2025

Our fourth newsletter is now available by download by clicking the link below - again it is in pdf format

Newsletter No 3 - July 2025

Our third newsletter is now available by download by clicking the link below - again it is in PDF format

Newsletter No 2 - June 2025

Our second newsletter is now available by download by clicking the link below, again it is PDF format.

Newsletter No 1 - April 2025

Today we have produced our first Newsletter, this is avaliable by download by clicking the link below, it is a pdf file so you may need to get a pdf reader is you haven't got a suitable reader on your device.

Our second article by Tom Walsh, again reprinted here with his permision

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF GOLD STREET, NORTHAMPTON

Northampton is a planned medieval town. Some of it, including Market Square, dates back to major restructuring in the mid-13th century, but earlier references to Gold Street (Aurifabris – Goldsmith’s) suggest this part dates back to the 12th century. Medieval layouts were based around the plots assigned to the burgesses, who were the main wealth producers. These plots were about an eighth of an acre, and were set out in blocks of about 20. The street pattern was determined around these, where there were no other structural factors. Remaining spaces were filled with smaller units for the lower classes, large units for wealthy landowners, and space given to monastic houses, churches and public buildings.

The planned medieval component of Northampton is very small, within an area about 500 metres east to west by 400 metres, dominated by the Market Square, with Gold Street forming the most substantial offshoot. The area extends from Horsemarket on the west to Fish Street on the east, and from Angel Street on the south to Greyfriars on the north. However the northern part, north of Bradshaw Street and Market Square, was substantially altered in the latter half of the 20th century. The western part includes St Katherine’s Churchyard and the site of the Dominican Friary under the Saxon/Moat House/Park Inn. The main surviving blocks of burgages are on both sides of Gold Street, the west side of Drapery, and on George Row. There are surviving fragments on St Giles’ Square, the westernmost ends of St Giles’ Street and Abington Street, and the east and north sides of Market Square. There are also some burgages on the west side of Bridge Street, which mostly has smaller units.

Consequently Gold Street, George Row and Drapery constitute the most important surviving evidence of the planned medieval town of Northampton. Of these, the Drapery has suffered from a number of insensitive late 20th century rebuilds, including Debenhams and MacDonalds. On Gold Street Brierleys, now the “99p store”, is the only major modern intrusion, there being some preserved façade on the entrance to the St Peter’s Square development, which had seen major changes as Jefferey’s Furniture Shop in the late 19th and 20th century. However it is apparent that Gold Street is about to change, as a result of speculative land purchases and development proposals, and a blight of dereliction and neglect. This account has been written as an attempt to circumvent the destruction of one of the most important elements of Northampton’s medieval heritage.

Burgages are the key property units of medieval town planning. Because of the work of W.G. Conzen and T. R. Slater, it is now known that medieval burgages often survive intact up to the present day, where there has not been significant late 20th century redevelopment. This is because the burgage is also a taxable unit, the basis of the medieval rating system. Property boundaries tended to stay fixed, because the rate stayed the same. This became very apparent after the Great Fire of 1675 when attempts to widen streets met with fierce resistance because the owners of the burgages did not want to give up land, because with a fixed rateable value, smaller plots would be harder to sell. However during the medieval period many of the burgages were divided lengthways into two halves, and occasionally into three. Most of the Gold Street burgages have been divided into two, though there are several apparent divisions into three.

Burgages were generally two falls wide, a fall being approximately 5 metres. To make up an eighth of an acre they are usually about five to six times as long. On Gold Street the burgages are mostly 10 metres wide and between 50 and 55 metres long, however near the Grand Hotel the entrance to Woolmonger Street, restricts the burgages to less than fifty metres long, and these seem to have been about 12 metres wide. Most half burgages are therefore about 5 metres wide, but at 43 Gold Street, on the south side, there appears to have been a division into three, with two of the units only 3 metres wide. What is so distinctive about Gold Street and Drapery are the number of surviving ‘half-burgage’ frontages, as well as distinct full burgages. Nineteenth and twentieth century rebuilds have occasionally combined frontages, but the regular unit widths define the pattern, which, even with modern rebuilds, gives rise to a great variety of facades. Modern developments tend to go for uniform frontages in concrete and glass, such as seen today on Abington Street.

Gold Street also has some smaller, shallower units, towards the east end, and several larger units, notably at the west end, such that the burgages stopped short of Horsemarket and Horseshoe Street. Originally the burgages had residential buildings gable end on to the street at the ‘head’ of the burgage, often incorporating a shop, and yards behind containing workshops. In the 18th and 19th century the yards were filled with extensions to the residential components, warehouses, factory premises and sometimes further residential development in the ‘tails’. Gold Street was also an important street for inns and hostelries, some recorded back to the 16th century.

The dominant characteristic of Gold Street is one of long narrow buildings, which have been very valuable, until recent times, as furniture, white goods and floor coverings retail outlets. Recently there has been an influx of pound shops and discount stores, but again what the street offers is floor capacity. There are generally two options with burgages: either to retain this capacity, which determines the retail functions, or restore the medieval pattern with most of the rear of the burgage open. With the latter option the tails often end up being used as car parks, but there are more effective ways of using them, to the enhancement of the town. Those with a street or rear access can be used as residential mews or for galleries and small shops, but these should be in keeping with the medieval layout. They can also provide gardens for restaurants and pubs.

The significance of Gold Street is that this medieval plan is largely intact. Along with the Drapery, which has burgages on the west and former shop units on the east side, Northampton has a superb heritage asset in the mixture of mostly narrow frontages in different styles, albeit these are mostly 19th and 20th century. Behind some of the facades, however, there may be older fabric. During several of the rebuilds in the first half of the 20th century on Gold Street, remains of wattle and daub and timber framing were found behind the more recent facades. However it is not just a matter of preserving facades. What is so significant is the survival of a medieval planned town, which means the whole burgage pattern is part of Northampton’s heritage, not just the street fronts.

On the south side of Gold Street, the block between Bridge Street and Kingswell Street was formerly two large burgages, but was reworked into smaller units as part of the Becket & Sargeant charity in the 18th century, forming shallower units to Gold Street, and east-west divisions from Bridge Street and Kingswell Street. The larger of the burgages, with its back gate facing Woolmonger Street, is well documented back to the 13th century, up until after the Great Fire of 1675, as a house with five shops or five bays. In the Town Rental of 1503-4 it was called “The Cardinal Hatte”, though this probably did not signify an inn. West of Kingswell Street, the second and third properties in 1503 belonged to St James’ Abbey, known as The Dolphin, an inn with a deed string up to the 19th century, remodelled in the 1880s as the Grand Hotel, and extended up to Kingswell Street. Originally it had an arched over coach entry from Gold Street, which was redesigned as the present front entrance. After the Grand Hotel the remainder of the south side is a patchwork of half-burgage fronts in different styles, with some later merged fronts, all contributing to a very attractive, if neglected, mosaic of architectural styles.

The mid part of the south side, around the modern entrance to the St Peter’s Square development, formed a group of three inns, dating back to the 16th century: The Psallet, later called the Swan & Helmet, The Windmill and The Rose. The Psallet can be traced back to 1544, but its owner then had the same surname as the owner of one of the burgages there in 1503. Numbers 47 and 49 Gold Street belonged to Cole’s Charity (1640), and for a time in the 18th century provided the vicarage for All Saints Church; it now forms Gold Street Mews. Number 51 was the house of Thomas Yeoman, inventor and engineer, and subsequently housed a society for scientific learning, and by the 19th century the Conservative Club. The west end of Gold Street is a much reworked manorial plot, and eight houses fronting Gold Street were built there in 1755, later reduced to six, and now entirely modern frontages. The manor house fronted Horseshoe Street, and was known as Stockwell Hall, last described in 1664; the site was used for All Saints Schools and Grose’s bicycle factory in the 19th century.

Similarly the burgages on the north side fell short of Horsemarket. and this was further complicated by the construction of a Methodist Chapel, early in the 19th century, across the rear yards of 42 to 48 Gold Street. This has since been superseded by a concrete and glass office block, now called Sol House, which extends behind some fairly shallow modern premises on Gold Street, through to Horsemarket. As a consequence 44 to 48 present rather impoverished two-storey frontages to Gold Street. Numbers 38 and 40 formed a town charity property, dating back to 1581. This was one of the earliest locations of Woolworth’s Stores in Northampton, and currently has a modern red brick frontage. Next to it, number 36, has a 1930s art deco façade; this partly overlaps the double burgage that was formerly an inn called The Goat, the remainder of which was entirely rebuilt in the 1970s as Brierley’s, now the ‘99p Store’. The Goat dates at least from the early 17th century, and two thirds of it burned down in the Great Fire of 1675, but it had ceased to be an inn by the late18th century. Although the Gold Street properties did not extend as far as St Katherine’s Street, The Goat acquired waste land from the town in 1755, to give it a rear access. There was formerly a plaque here commemorating the site of the Goat, but it has been covered over by the latest shop front.

Numbers 24 to 36 Gold Street have had a rather complex history back to 1611, when they belonged to the Hoe family of Upton, and probably originate as two properties acquired by the Dominican Friary in the 14th century. Chief of these, number 30, was the Rose & Crown Inn up until about 1900. Number 32 is the site of the Three Tuns, while numbers 26 and 28 formed the Wheatsheaf, later the White Hart. The Rose & Crown enjoyed the benefit of a plot of land, part of Cole’s Charity, on St Katherine’s Street, but lost this after a court case over the rent in 1812. Number 32 has a rather unusual frontage; Wilkinson’s is in a rebuild that at one time housed Marks & Spencer’s. The remaining properties to College Street were curtailed northwards by part of Cole’s Charity, which appears previously to have been the site of the College of All Saints. Thus the corner property with College Street was a garden, containing a building called the storehouse or spice house, dating back to the 16th century or earlier. This was divided into three premises fronting Gold Street in the 19th century, and several behind fronting College Street.

The block between College Street and Drapery is most unusual, and comprised several burgages which extended to Friends Lane, now much reduced as Jeyes Jetty, and some smaller properties. The modern corner with College Street, formerly the Queen’s Head, a 19th century public house, and the colonnaded frontage next to it, the western part of Litten Tree, are shallow buildings. Next to it, Greene’s Charity, has a very different and rather neglected façade, which only measures 12.5 feet to Gold Street, and is only 18 feet deep, mostly lost to the arcaded pavement here. Dating back to 1640, it figures prominently in the ‘Vernall’s Inquests’, a section of the Borough Records which deals with boundary disputes in the late 17th century, and in the 18th and 19th century was known as ‘the front of the Bull & Goat’ in charity accounts.

Next east is one of the most remarkable frontages on Gold Street, although only a late 19th century creation, which was the head office of Phipps & Co brewers up until the 1930s. Now arcaded as part of the pavement at the front, this extended back to Jeyes Jetty. Though having burgage width, it is less than 35 metres deep. In the 19th century it incorporated a charity property on the south side of the Jetty towards College Street. Along with its neighbour, which is part of the set-back premises, formerly Belfast Linen, now Circus, it formed the inn known as The Greyhound, and later as the Bull & Goat. This dates back to 1654, but was probably the inn known as The Harp, recorded back to 1540. A narrow strip of land 5 feet wide and 18 feet long, on the east side, belonged to St John’s Hospital, but evidence suggests this is a residue of a larger property, misappropriated during the Civil War, which included the Chapel of St Mary Magdalene. The remainder of the corner with Drapery has been much reduced, firstly after the Great Fire of 1675, and then in the 20th century, to facilitate traffic. When it was rebuilt after the Fire, carved stones in the form of branches of fruit were incorporated in the façade, which supposedly had come from Holdenby House, when it was destroyed in 1650, but mid-19th century, when the corner house was rebuilt, the carvings were destroyed.

Dr Thomas C. Welsh 1st October 2006

This is an article previously published by Tom Walsh, now reprinted here with his permission

NORTHAMPTON TOWN CENTRE

MAIN HERITAGE FEATURES

Market Square. This extends west across Drapery and south to George Row, to include All Saints Church. The buildings east of The Drapery and north of All Saints were originally shop stalls within the market area. Most of these are very small (many about 6 metres long and 3-4 metres wide), with no garden or yard space. The larger premises with ornamented frontages on the south side of the modern square were built after the Great Fire of 1675 on the site of the butchers’ rows. Rentals dating from around 1300 and 1503-4 give details of these shops, and we know where different market functions were located. The north and east sides of the square were medieval burgages, residential units with long rear yards, originally 10 metres wide and 60 metres long, but most of this pattern has been lost through 1960s and 70s rebuilds.

The Drapery. Formerly called The Parmentery, the west side is made up of burgage plots, except south of Jeyes Jetty (where again they are tiny shops) and the corner with Bradshaw Street. The east side is made up of tiny shop units, which were within the Market Square, the Drapery being known as the Ladies’ Market. Midway on the west side is the jetty formed through a large medieval inn called The Swan, which was broken into smaller units in the 18th century. Much of the character of The Drapery has survived, even if many of the frontages are modern, with the exception of uncharacteristic intrusions like Debenhams and MacDonalds. It is desirable to retain this mix of frontages and avoid further incongruous modernities, as this is one of the most important historic streets in the town.

George Row. This is also a valuable heritage frontage, made up of large burgages, extended in length by absorption of a former lane to reach to Angel Street. This street and its continuation onto St Giles Square, contained most large medieval inns. The bank on the corner of Bridge Street occupies the site of the George, which was originally three inns – The George, The Bull and the Forge. The others were The Tabard and The Bell, rebuilt as County Hall, and The Crown (more recently known as The Judges’ Lodgings). In between was a mansion house, later the first hospital and now the County Club.

Abington Street. The lower part, below Waterloo Street, was very narrow, corresponding to the present north side pavement, and was widened southwards in the 1930s. The medieval Guildhall stood on the south corner with Wood Hill. The upper part seems always to have been wide, the north side belonging to the Carmelite Friary and divided into private house plots in the 18th century. The south side belonged mostly to the Gobion Manor, the manor house standing where the west half of the former Co-op building now stands. The Gobion Manor leased small plots either side as cottages. The upper part of Abington Street has been extensively rebuilt in the 20th century with large frontages. There is very little historic character left, and it could be regenerated without heritage concerns.

St Giles Square. Although the Guildhall replaced fine town houses on the north side, it is obviously the gem of the town, and is equally graced by the south side counterpart, which also featured large town houses. The jewel here is the Constable’s House, which had symmetrical wings, now a restaurant. However part of the jewel is spoiled because the modern annexe of the public house The Old Bank (formerly a bank) hides one of the wings.

St Giles Street. This only extended as far as Fish Street in medieval times, and a few burgages survive on the north side, and there was a manorial property, Little Holdenby, where the post office stands. Eastwards there were manorial properties either side; Gobion Manor north and The Tower property south. It was only developed in the 18th and 19th century, except for a few houses at the St Giles Church end, but this is what gives it its charm, as it is quite contrasting to the medieval town, and a valuable heritage street, bar one or two ill-judged intrusions, such as the medical centre and CAB. An 1864 rebuild of Massingbeard’s Charity Houses 1680 is a particular gem.

Dychurch Lane. This originally extended to Wood Hill, and was diverted onto Abington Street after the Great Fire. It may be an early street, older than Abington Street and St Giles Street, and is actually on the line of the original route to Abington and Weston Favell. Its earlier names were Dithers Lane, Grope Lane and originally Gropecunt Lane.

Derngate. Some fine buildings at the upper end, but again, east of Swan Street was manorial land up until the 18th century, and what survives is a mix of 18th and 19th century terraces and large modern intrusions.

Bridge Street. This seems to have been a 13th century intrusion replacing an earlier street pattern, and the properties either side are very shallow. It cuts through the original precinct of St John’s Hospital and may explain the off-cut west end of St John’s, the oldest non-church building in Northampton, and one of its finest gems. The attraction of the upper part of Bridge Street are the inns, now mostly estate agents, while lower down the Charity School, now a restaurant, and other old buildings are important.

Gold Street. This street, despite its currently run-down appearance, is very important in heritage terms because medieval burgages survive both sides, most of these, even if later amalgamated in rebuilds, being half burgages, 5 metres wide. They create a distinctive mix of frontages, although mostly late 19th and 20th century. The long plots were important as warehouses and large goods shops in the 19th and early 20th century, but do not suit modern delivery vehicles. However these long plots are a crucial part of the street’s character and should be considered in any redevelopment.

Sheep Street. This street contains a number of very fine 18th century town houses, built by William Kerr and his associate, founders of Northampton General Hospital.

21st November 2007

Northampton's Historic Gathering Places

The Mayor of Northampton called a meeting of all interested town heritage groups in the Guildhall last Friday, 18th October. The meeting lasted 90 minutes with 6 speakers giving short presentations, followed by much debate. The core of the meeting was to raise the problems with the Heritage Buildings within Northampton and what is going to happen to them - examples - The Town Council are being asked to move out of theb Guildhall - the seat of local democracy for hundreds of years, the Guildhall Extension is now empty - so what are WNC's plans for the site, also we have the Sessions House and County Hall in the town centre at risk of being sold/leased to help WNC's financial difficulties, but WNC have paid millions for the St James Tram and Bus Depot and now the old Corn Exchange on the top of the Market Square.

More details will follow on from the meeting in the next week or so.

Sept 22nd 2024

Sept 16th 2024

June 2024

Northampton’s Building in Stone

With Bob Purser

17th June 7:30

Humfrey Rooms, Castilian Terrace, Northampton

Northampton townscape reflects the rich variety of the local Jurassic geology, to which exotic rocks from further afield can be added, often representing 'corporate architecture as represented by the Marks and Spencer building. Bob Purser from the geology section of the Northamptonshire Natural History Society will relate our many fine buildings to this geology.

We kindly ask a for a suggested donation of £5 pp to cover the cost of renting the hall

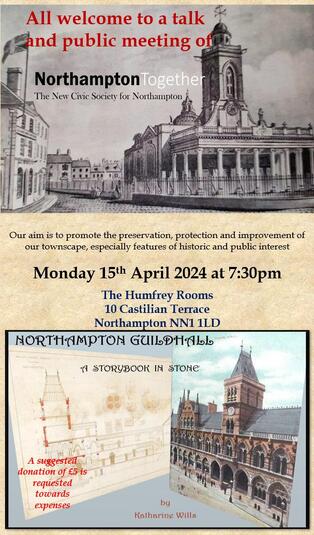

April 2024

Our first talk of the year - details shown here. We would welcome anyone with an interest in the history of the town to come along to our talks.

Jan/Feb/Mar 2024

Planning Applications in progress - for more information go to the WNDC Planning web site and make your comments to them direct before the closing dates shown on the application details on-line - or click on the link below. Updated 21 May 2024

WNDC/2022/1055 - Overstone Hall - Proposed Demolition of - Target Decision date 29th Feb 2024 <<< Still Pending - Decision supposed to be end of April - Now 2nd May and Planning Web Site still says Pending

2024/0367/FULL - Car Park Surface N B C, Chalk Lane, - Creation of a new heritage park on the site of the former Chalk Lane car park. Works involve, removal of existing car park, adjustment's to Castle Mound, hard and soft landscape works, the provision of a new playground area, community gardens, lighting fencing, heritage features and story boards and new seat walls. - Target Decision date now 10 May 2024 <<<< Approved 14th May

Northampton's Heritage Buildings

We at the Society are concerned at the way WNDC are even thinking about disposing of some of the most historic buildings in the town. What makes it worse is the admission that some of the buildings are in 'poor condition', something the Council should be looking after as part of its work, especially when some of the buildings are Grade 1 listed. The BBC News page is reprinted here :-

Plans are being drawn up to sell historic buildings in a town centre.

West Northamptonshire Council (WNC) said Northampton's County Hall and other nearby properties were in a poor condition and were not "effective for modern operational need".

Much of the space was no longer used after eight Northamptonshire councils were reduced to two in 2021.

WNC said the buildings would be offered on long leases to "retain a degree of control" over their future.

A report to WNC's cabinet said: "It is clear that the council has a surplus of office and administrative meeting rooms, and we are not making the best use of the space we have in terms of value for money."

It added the buildings in Northampton were "a cherished heritage asset" and their long-term futures should be "secured".

The Grade I listed Sessions House, with its familiar facade on George Row, was completed in 1678 after the Great Fire of Northampton and was a functioning court until 1987.

The report said this could be leased to commercial food and drink operations, and there was some scope for tours of courtrooms and cells.